Last week we did a bit of housekeeping over on our website. We last updated it shortly after I went back to self employed life, when we didn’t know which strands of our work would gain momentum and significance. Now things are a (little) bit clearer, it felt like time for a re-jig.

One thing in particular that needed a bit of a sort out was the woodcraft section. Woodworking didn’t end up taking up as much of my time as I thought it might, but I have had the chance to learn some new skills and work on some rewarding projects and I felt it wise to bring them all together in one place.

Curating a collection of photos from recent woodworking projects got me thinking about my relationship with wood, trees and woodlands so I thought I’d jot them down here.

Do you have a connection to a material as a craftsperson? Or perhaps to something that has given you more than you were seeking? If so we’d love to hear about it in the comments or you can email us.

Few things have taught me more about Nature than working with wood. To understand the material, you have to understand trees and how they grow, and to understand trees you have to consider the whole of Nature, from the simplest single cell organisms to unfathomable vastness of the entire universe. To work with wood, is to work directly with the fabric of the universe; cells and fibrous vessels woven by the rotating earth, cycles of light and dark, summer and winter, storm and drought. In this way, each single strand of vascular tissue is a physical connection to the entire cosmos.

When speaking about woodworking here, I mean carving or working with green (that is, freshly felled) wood with simple, sharper than a razor, hand tools. This approach encourages a deep connection to the material that I don’t think working with sawn timber can provide; for one, it is normally the maker that also fells the tree. Wood recently cut is still full of sap, heavy, cool and fresh, fragrant and crisp. It is still very much tree rather than timber. Well looked after tools slice effortlessly into the soft unseasoned meat of the tree, carving ghost-like slithers of wood, thin enough to see light through. As you work, quietly carving away, with no dust or noise from power tools, the quiet ssssshk ssssshk of the knife removing material is meditative, allowing time for contemplation and silence that can be accompanied by birdsong or leaves rustling in the breeze.

Cleaving, the art of splitting a piece of wood along its length is best undertaken when wood is green too; wedges will rive green wood apart in halves, then quarters, then eighths, all the way along full tree lengths, the split following natural weaknesses between layers of cellular growth. Success requires a sensitivity to the way the tree has grown, a willingness to work with its inherent structure and form.

In searching for wood to work with, I started to notice for the first time the connectedness between all things in the woods. No tree could be thought of as singular; each one was the product of its relationship with its neighbours, with the soil, fungi, wind, sun, bird, bug and beast. Trees on the edges of woodlands or in fields had low, spreading branches while those grown close to others were tall and straight with minimal side branching. Some would bend towards openings in the canopy, others were sculpted over time by prevailing winds. Studying the form of trees allowed me to be able to read a patch of woodland like a book, to know its history and to make guesses as to what lay in its future. In studying wood itself, which consists of many different groups of cells all doing different jobs to benefit the tree as a whole, I began to question whether we should think of trees as individuals or rather as a collaborative group of separate organisms working symbiotically. My own impact on the woods was not lost on me either; each time I harvested material, I was able to watch how woodland life responded. The gaps I created were soon occupied by pioneering types, jostling and competing for access to the light. I too became part of the woodland ecosystem.

It turned out that trees were providing me with much more than just a material to work with, they were teaching me new ways of seeing things, new ways of living even. In time, simply being in the woods became more important than the act of making things from something that came from the woods.

It is without doubt that living in the woods allowed me to become so fully intertwined with such a wonderful material, but wood has been part of my life for many years. My Dad is a skilled woodworker, making everything from actual planes that fly to exquisite archtop guitars with an accuracy far beyond that which I can achieve with axe and knife. Although I’m self taught, just having been around wood and woodworking whilst growing up is no doubt part of the story and for that I’ll always be thankful.

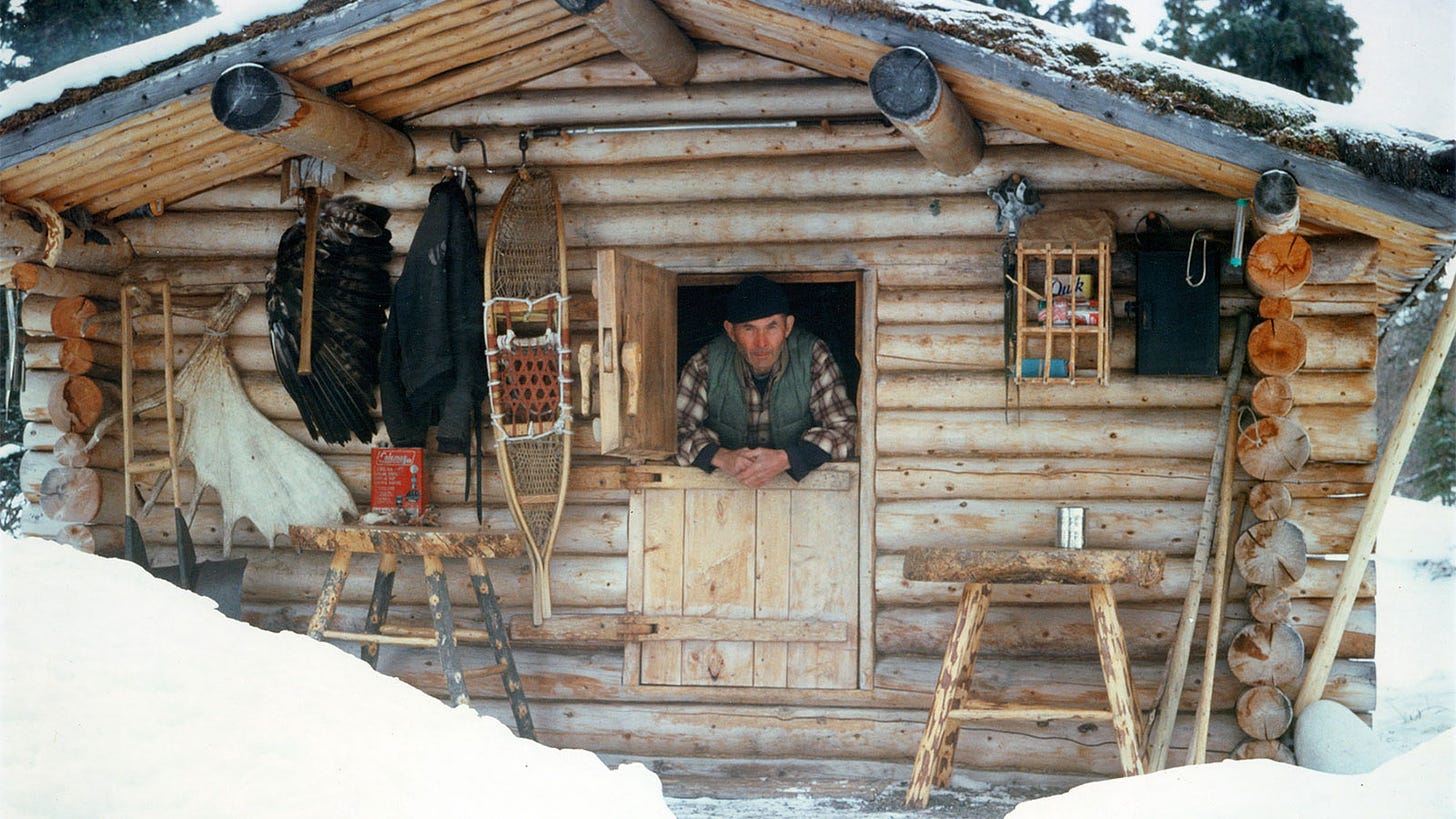

When starting out as an outdoors person, I devoured documentaries and books about those living in remote wilderness areas of Alaska, Canada, and Scandinavia. The idea of living off grid, relying on your own skills and connection to the land to thrive appealed to me greatly. There was one story in particular that I have to thank for inspiring me to pick up an axe and start making things with seriousness: Alone in the Wilderness, featuring Dick Proenneke.

Some of you will already know, but this film documents the extraordinary life of Dick Proenneke as he moves (at age 51) to Twin Lakes, Alaska and builds himself a cabin where he lives for 30 years. What makes this story stand out from others is Dick’s remarkable skill as a woodworker. The cabin he builds, and the items he makes to help him live in comfort in the wilderness are not only functional but also beautiful, crafted with precision and utmost care, despite being made with a heavy double bit axe, knife and saw. If you haven’t seen it, I recommend tracking it down, but be warned, you may suddenly wish to leave society behind for good and head to the wilderness…

The woods of Sussex are a far cry from the wilds of Alaska, but Dick’s ingenuity, self reliance, sensitivity to the land and enviable craftsmanship provided inspiration aplenty for me as a woodworker and on my own journey living a life closer to Nature.

Each time I’m at the chopping block, reassuring weight of axe in hand, chips piling up at my feet, I carry this whole story with me. I hope too, perhaps, that each item I make carries the spirit of this journey and manages to retain a little magic from the woods and a connection to the cosmos.

In closing, I think I’ll leave you with a quote from The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R Tolkien that I think of often when I’m working with wood:

"Never before had he been so keenly aware of the feel and texture of a tree’s skin and of the life within it. He felt a delight in wood and at the touch of it, neither as a forester nor as a carpenter; it was the delight of the living tree itself."

Well, that’s all for this week. Did you see our latest Nature Happenings? This was the first one that we sent as a stand alone publication, so we'd love to know what you think.

With warm wishes, as always,

Andrew, Emma and Benji

x